„Zeugnisse für das Recht aufs Anderssein“: Die Fotografin Libuše Jarcovjáková

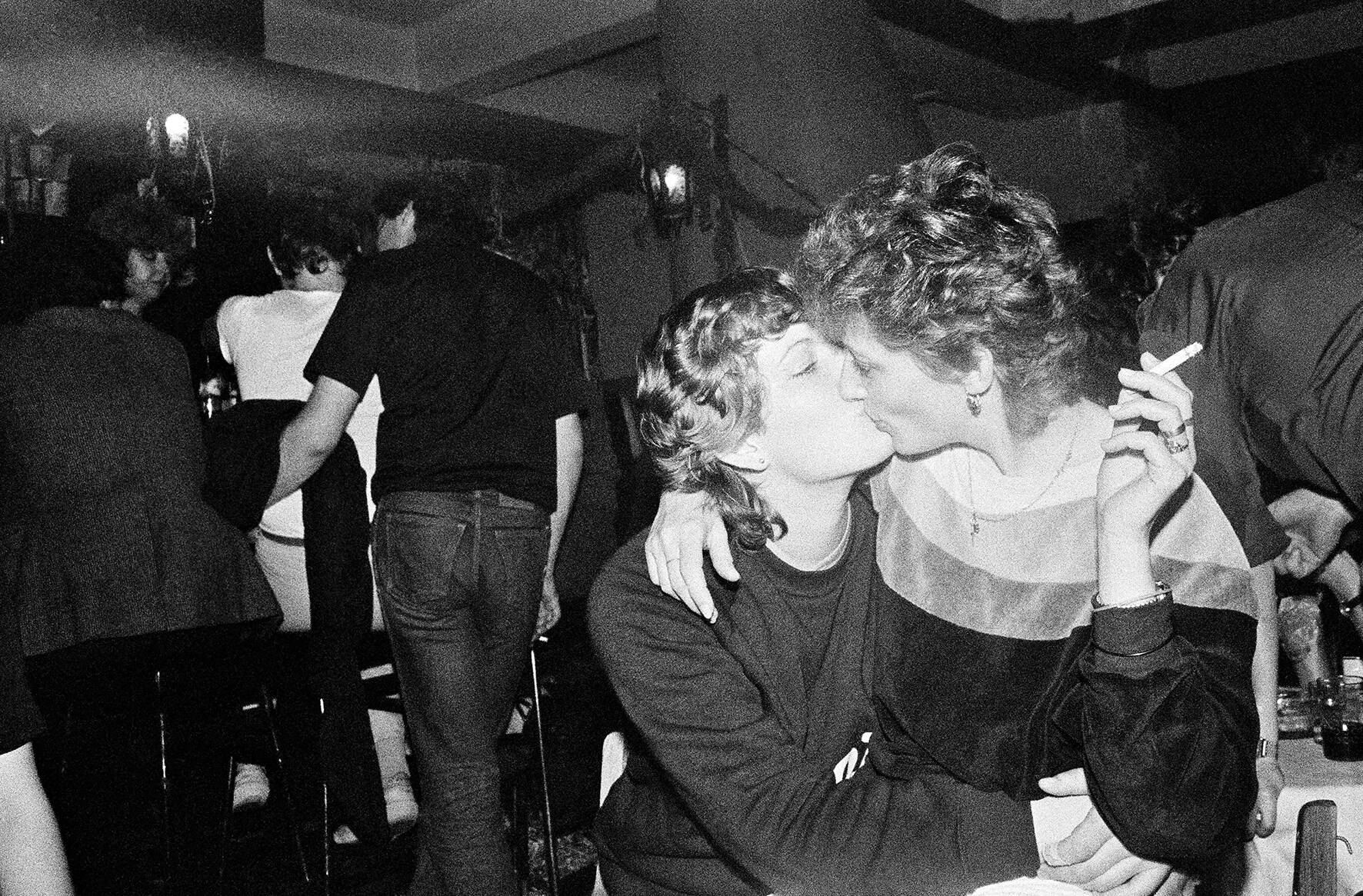

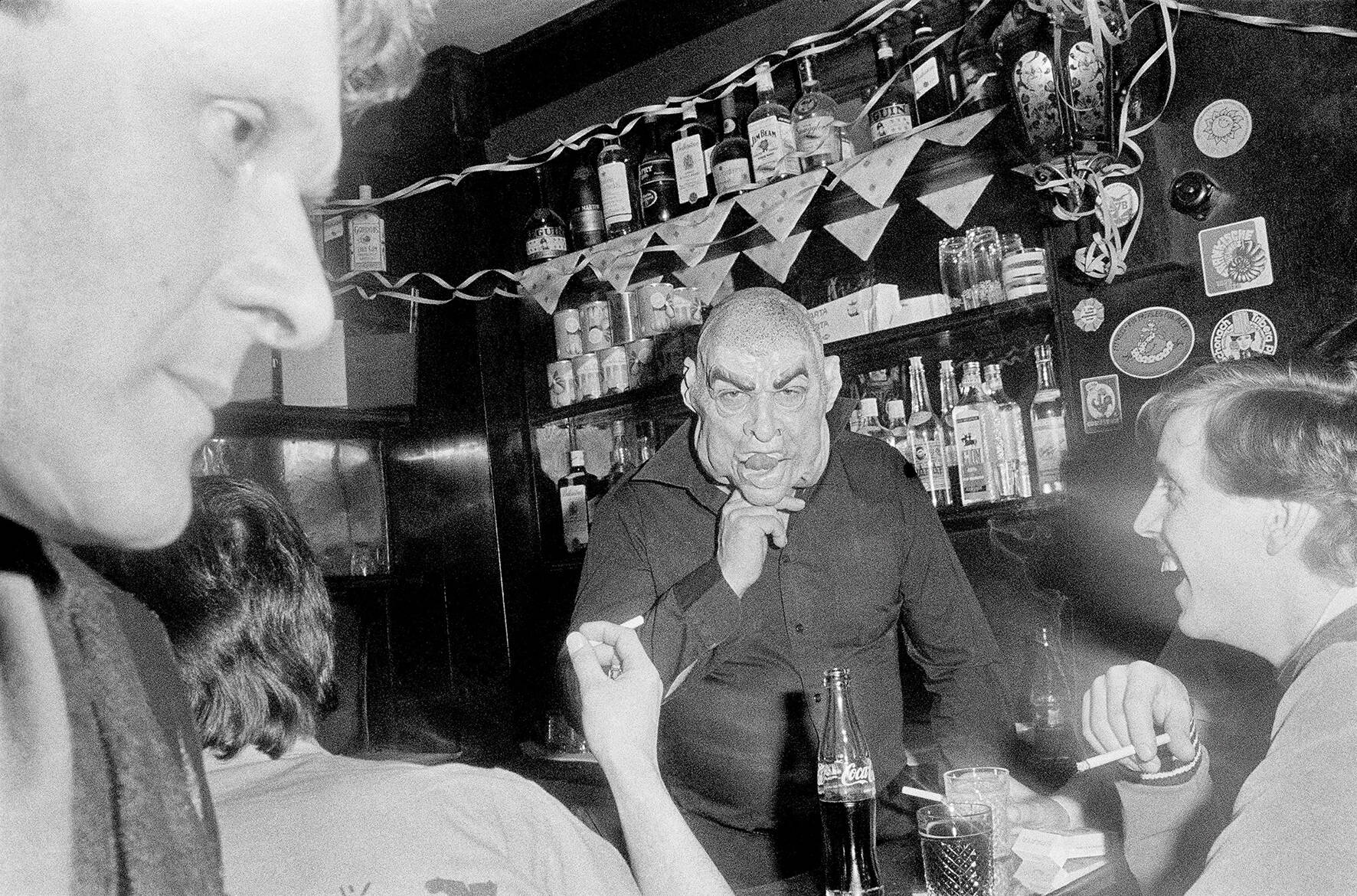

„Noch bin ich nicht, wer ich sein möchte“ lautet der Titel eines Dokumentarfilms über die tschechische Fotografin Libuše Jarcovjáková, der jetzt in die deutschen Kinos kommt. Der eindrucksvolle Film von Klára Tasovská ist eine Montage aus unzähligen, teilweise rhythmisch arrangierten Fotos und den von Jarcovjáková selbst eingesprochenen Tagebucheinträgen. Bilder und Texte folgen einer fortlaufenden Selbstsuche: Mit der Zerschlagung des Prager Frühlings beginnt die damals 16-Jährige zu fotografieren. In der Fabrik, in Kneipen, Privaträumen und auch Nachtclubs entwickelt sie eine Schnappschuss-Ästhetik, die Menschen vom Rand der Gesellschaft in den Fokus rückt: queere Menschen, Migrant*innen, unangepasste Frauen, Dissident*innen. Und ohne jede Eitelkeit richtet sie ihre Kamera unermüdlich auf sich selbst. Von Prag über Tokio führt ihr Weg auch immer wieder nach Berlin, wo nun eine Ausstellung ihre Fotos aus dem queeren T-Club zeigt. Wir sprachen mit Libuše Jarcovjáková über selbstverständliche Queerness, feministische Anliegen und die widerständige Kraft der Fotografie.

Interview mit Libuše Jarcovjáková

Sie haben in verschiedenen Ländern und Systemen gelebt und gearbeitet. Welchen Einfluss hat das auf Ihr Selbstverständnis als Fotografin gehabt?

Libuše Jarcovjáková: Seit meiner frühen Jugend stellte mir oft Fragen zu meiner Identität, zum Sinn des Lebens und suchte nach dem, was ich bin und wohin ich gehe. Zum Glück hatte ich zwei Werkzeuge, die mir halfen, Antworten zu finden: Tagebuchschreiben und Fotografieren. Für mich war die Kamera nicht nur ein Fenster, durch das ich die Welt betrachtete. Oft wurde sie auch zu einem Spiegel, der mir persönliche Botschaften lieferte. Meine Fotografie ist das Ergebnis meiner ständigen Suche.

Die verschiedenen kulturellen und politischen Kontexte – von den hoffnungsvollen Momenten des Prager Frühlings über das Leben in der Grauzone des realen Sozialismus mit all seinen alltäglichen Hindernissen bis hin zur Energie Tokios in perfektem Design und der transformativen Euphorie nach dem Fall der Berliner Mauer – all das hat meine Selbstbild tiefgreifend beeinflusst. Jedes System hat es mir ermöglicht, meine Identität, meine Werte und meine Möglichkeiten zu erweitern. Meine Arbeit prägt das ständige Bemühen, die sich ständig verändernde Wahrheit der menschlichen Existenz einzufangen. Bei der Fotografie geht es nicht nur darum, hinter einem Objektiv zu sitzen, sondern um ein tiefe Beziehungen zur Umwelt und zu sich selbst.

So sind auch Ihre vielen Selbstporträts ein wiederkehrendes Motiv in dem Film. Was bedeuten diese Bilder für Sie?

Libuše Jarcovjáková: Meine Selbstporträts entstanden als Mittel zur ständigen Konfrontation mit den vielen Schichten meines Wesens – als eine Möglichkeit, mich mit meiner Körperlichkeit zu verbinden und mit den persönlichen und gesellschaftlichen Traumata fertig zu werden, die ich, wie wir alle, durchgemacht habe. Es sind Botschaften über meine Präsenz, meine Verletzlichkeit und meine Transformation.

Viele Jahre lang habe ich sie ausschließlich für mich selbst geschaffen, ohne zu ahnen, dass sie eines Tages öffentlich werden und ein Zeugnis von der menschlichen Existenz ablegen würden. Der Film bietet nun die Möglichkeit, an meiner Selbstfindungsreise teilzunehmen – manchmal gelingt das, manchmal nicht.

Der Film erzählt von Ihren Schwangerschaftsabbrüchen, einer legalen und einer heimlichen. War es für Sie – und die Regisseurin Klára Tasovská – ein feministisches Anliegen, dies so offen darzustellen?

Libuše Jarcovjáková: Die Geschichte meiner Schwangerschaftsabbrüche ist höchst persönlich, aber auch unweigerlich politisch. Das Thema war für mich immer schmerzhaft und es fiel mir schwer, diese Erfahrungen mit einem Publikum zu teilen. Aber es geht um die körperlichen und emotionalen Auswirkungen einer Gesellschaft, die den Körper von Frauen und ihre Entscheidungen oft reglementiert. Für mich war es ein wahrhaft feministischer Akt, mich dieser rauen Wahrheit öffentlich zu stellen. Im Gespräch kamen Klára und ich zu dem Schluss, dass dieses Thema immer noch aktuell ist und jede Selbstzensur die Essenz des Films verändern würde. Diese Geschichte ist nicht nur eine Aussage über mich, sondern auch über die vielen Frauen, die sich damals und heute in ähnlichen Situationen befinden.

Ihre Kamera ist sowohl Ihrem Körper als auch den Körpern Ihrer Liebhaber*innen sehr nahe. Im Film scheint es so, als wäre es für Sie ganz natürlich, auch mit Frauen zu schlafen und sich schließlich in eine zu verlieben.

Libuše Jarcovjáková: Sexualität – fließend, vielschichtig und sich Kategorien entziehend – war schon immer ein wesentlicher Bestandteil meiner Arbeit und meines Lebens. Die Intimität meiner Linse, ob ich nun meine eigene Gestalt oder die Körper und Formen meiner Geliebten einfange, diente mir als Mittel zur Erforschung von Begehren, Verbindung, Liebe, Freundschaft und Menschlichkeit. Bei meinen Erfahrungen mit Frauen und der Liebe, die aus diesen Begegnungen erwuchs, ging es nie darum, Erwartungen zu erfüllen. Ich umarmte eine Bandbreite von Gefühlen, die sich konventionellen Etiketten entziehen, und wollte die ganze Komplexität der menschlichen Existenz ausdrücken. Wenn das seltsam erscheint, kann ich nichts dagegen tun. Ich persönlich empfinde es als sehr natürlich.

Libuše JarcovjákováSexualität – fließend, vielschichtig und sich Kategorien entziehend – war schon immer ein wesentlicher Bestandteil meiner Arbeit und meines Lebens.

Im sozialistischen Prag, so erzählt der Film, haben Sie erlebt, wie Ihre Fotos zu einer Waffe in den Händen des Staates wurden: Die Bilder des queeren T-Clubs wurden von der Polizei benutzt. Könnte Ihre Arbeit auch eine Waffe gegen den Staat gewesen sein? Hatten Sie eine Verbindung zur Opposition?

Libuše Jarcovjáková: Als mir klar wurde, dass meine Fotos von der Staatspolizei gegen die Menschen, die ich fotografiert hatte, verwendet werden könnten, beschloss ich, das Fotoprojekt im T-Club sofort zu beenden. Zu diesem Zeitpunkt war ich bereits auf dem Weg nach West-Berlin, so dass kein größerer Schaden entstanden ist. Die Personen, mit denen ich in Kontakt stand, waren damals in offener Opposition zum Regime. Wir waren gut informiert und verfolgten aufmerksam die Nachrichten aus dem Westen über ausländische Medien. Ich vermied streng jegliche engagierte Stellungnahme oder Zusammenarbeit mit dem Regime und kannte eine Reihe von Dissident*innen, aber ich wurde nie direkt Teil dieser Bewegung.

Die Fotos aus dem T-Club sind in einem Buch veröffentlicht worden und werden jetzt in einer Ausstellung in Berlin gezeigt. Sind sie hier noch politisch?

Libuše Jarcovjáková: Im Moment scheint es, dass meine Fotos aus dem T-Club nur eine unschuldige, nostalgische Erinnerung an ein etwas unerwartetes Phänomen im Rahmen des realen Sozialismus im Prag der 1980er Jahre sind. Obwohl ihr ursprünglicher Kontext stark politisch war, hoffe ich, dass sie heute zum Zeugnis für das Recht aufs Anderssein werden, ohne dieses Recht erneut verteidigen zu müssen.

Libuše JarcovjákováIch hoffe, dass meine Fotografien heute als Zeugnis für das Recht aufs Anderssein verstanden werden.

Im Prag Ihrer Jugend fehlte Ihnen die Freiheit, von Tokio aus sehnten Sie sich nach Kreativität. Beides haben Sie in West-Berlin gesucht. Konnten Sie dort beides finden? Welche Bedeutung hat Berlin heute für Sie?

Libuše Jarcovjáková: Berlin war für mich eine große Herausforderung, als ich Mitte der 1980er Jahre dorthin zog – ohne Sprachkenntnisse, Freund*innen, Geld und mit minimalen Wissen darüber, was das Leben im Westen bedeutet. Ich überwand alle Hindernisse und profitierte von den unglaublichen Ressourcen der Stadt. Mich fasziniert die Multikulturalität, Kunst und Freiheit, die Berlin ausstrahlte trotz der vielen Kriegsnarben, die sie damals noch trug. Berlin ist für mich eine Stadt, die mich nie verlässt, weder mit ihren Widersprüchen noch mit ihrer ständigen Entwicklung und Offenheit. Es ist eine Stadt, die mich immer wieder herausfordert, mich als Künstlerin und Mensch weiterzuentwickeln.

Der Film über Sie und Ihre Fotografie entstand mitten in der Pandemie und ist nun seit einem Jahr auf Festivals unterwegs. Welche Erlebnisse hatten Sie seitdem mit ihm?

Libuše Jarcovjáková: Der Film hat ein Eigenleben entwickelt, während er von Festival zu Festival reist. Jede Vorführung eröffnet neue Diskussionen, löst unerwartete emotionale Reaktionen aus und bringt manchmal sogar Menschen dort zusammen, wo sich persönliche Geschichte und kollektive Erinnerung überschneiden und sie Trost oder Inspiration finden. Ich bin immer wieder erstaunt, wie viele Menschen aus verschiedenen Ländern sich mit Ebenen des Films identifizieren können. Die große Bandbreite der Reaktionen bestätigt, dass uns ein Film zu universellen Themen des Leben gelungen ist.

Wie geht es weiter bei Ihnen?

Libuše Jarcovjáková: Für mich ist es wichtig, bei Verstand zu bleiben und mir die Fähigkeit zu bewahren, die Welt in all ihren Nuancen wahrzunehmen. Mit Kreativität, Fotografie und Schreiben wehre ich mich gegen übermäßigen Pessimismus und Skepsis gegenüber der Gegenwart. Ich versuche, nicht der berauschenden Informationsflut zu erliegen, und bleibe stattdessen kreativ, um eine authentische Perspektive auf das Leben zu wahren und meine inneren Erfahrungen auszudrücken.

Libuše JarcovjákováMit Kreativität, Fotografie und Schreiben wehre ich mich gegen übermäßigen Pessimismus und Skepsis gegenüber der Gegenwart.

„Noch bin ich nicht, wer ich sein möchte“, Tschechien/Slowakei/Österreich 2024, Regie: Klára Tasovská, 90 Minuten, tschechische Originalfassung mit deutschen Untertiteln, FSK: 16, Kinostart: 27. Februar 2025. Termine und Filmgespräche. Vom 27. Februar bis 19. April 2025 wird „T-Club – Just Like in Paradise“ im KVOST Berlin gezeigt. Die Ausstellung ist eine Kooperation mit dem Tschechischen Zentrum Berlin und dem Verlag untitled, bei dem der dazugehörende Bildband erschien, und wird präsentiert im Rahmen des EMOP Berlin 2025.

Original Interview with Libuše Jarcovjáková

You have photographed in different countries and systems. What influence did this have on your self-image as a photographer?

Libuše Jarcovjáková: Since my early youth, I have had a great need for self-exploration and have often asked myself questions about my own identity, the meaning of life, and searched for where I am and where I am going. Fortunately, I had two tools at my disposal that helped me find answers: journaling and photography. Both of these intimate tools helped me get closer to myself, to draw deeper understandings, and thereby find answers. For me, the camera was not just a tool for documenting the world around me, it was not just a window and an eye through which I look at the world. Very often it also became a mirror that provided me with personal messages. My photographic work is a direct result of my constant search.

Working in various cultural and political environments – from the hopeful moments of the Prague Spring, to life in the gray zone of real socialism with all its everyday obstructions, to the energy of Tokyo in perfect design, to the transformative euphoria after the fall of the Berlin Wall – has profoundly influenced my self-perception. Each system and each country offered me a unique perspective that allowed me to push my own identity, values, and creative possibilities. These diverse experiences showed me that my work is not defined by a single style or geographical framework, but by a constant effort to capture the changing truth of human existence, which is constantly evolving. This experience showed me that photography is not just about sitting behind a lens, but about establishing deep relationships with the environment and oneself.

Your many self-portraits are a recurring motif in the film. How would you describe the importance of these portraits?

Libuše Jarcovjáková: My self-portraits were created as a means of constantly confronting the many layers of my own being – as a way of reconnecting with my physicality and coming to terms with the personal and societal traumas, the cyclical waves that I, like all of us, have gone through. They are messages about my presence, vulnerability and transformation. For many years I created them exclusively for myself, never suspecting that one day they would become a public domain, capable of bearing universal witness to the diversity of the world and human existence. Thanks to the film, the viewer now has the opportunity to join my journey of self-discovery – sometimes they succeed, sometimes they may not, but it is always an open dialogue between my inner reality and the world around us.

The film tells the story of your abortions, one legal and one in secret. Was it a feminist concern for you – and the director Klára Tasovská – to portray this so openly?

Libuše Jarcovjáková: The story of my abortions is deeply personal, but also inevitably political. The topic of abortion has always been painful for me, and opening this experience to an audience was very challenging. By sharing these moments, I faced the physical and emotional impacts of a society that often regulates women’s bodies and their decisions. For me, it was a truly feminist act – to face this raw and painful truth publicly. When Klára and I talked about these issues, we came to the conclusion that this is still a very relevant topic and any self-censorship would change the essence of the film. Klára and I believed that this story would be a statement not only about me, but also about the many women who found themselves in similar situations, then and now.

Your sexuality is an important theme for your photography. Your camera is close to both your body and the bodies of your male and female lovers. In the movie, it seems like it was natural for you to sleep with women and eventually fall in love with one.

Libuše Jarcovjáková: Sexuality—fluid, multi-layered, and often defying strict categorization—has always been an integral part of my work and my life. The intimacy of my lens, whether capturing my own form or the bodies and forms of my lovers, has served as a means of exploring desire, connection, love, friendship, and humanity. My experiences with women, and the love that grew from those encounters, have never been about fulfilling expectations or ticking boxes. They have been about honestly embracing a range of feelings that defy conventional labels, and about expressing more deeply the authentic complexity of human existence. If that seems weird, there’s nothing I can do about it. Personally, it feels very natural and completely normal to me.

In socialist Prague, as the film tells us, you experienced how your photos became a weapon in the hands of the state: the pictures from the queer T-Club were used by the police. Could your work also have been a weapon against the state? Did you have any connection to the opposition?

Libuše Jarcovjáková: The moment I realized that my photos could be misused by the state police and used against the people I photographed, I decided to immediately end the photography project at the T-Club. At that time, I was already on my way to West Berlin, so no major damage was done. The people I was in contact with were in open opposition to the regime at the time – we were well informed and closely followed the news from the West, which we received through foreign media. I was very careful to avoid any committed statements or collaboration with the regime. I knew a number of people from the dissident movement, but I never became a direct part of it.

The photos from the T-Club have been published in a book and are now shown at an exhibition in Berlin. Are they still political here?

Libuše Jarcovjáková: At the moment, it seems that my photographs from the T-Club may be just an innocent, nostalgic reminder of a somewhat unexpected phenomenon within the framework of real socialism in Prague in the 1980s. Although their original context was strongly political, today I hope they will become a testimony to the right to be different, without having to defend the right to be different again.

In the Prague of your youth you lacked freedom, from Tokyo you yearned for creativity. You sought both in (then West) Berlin. Were you able to find both there? What does Berlin mean to you today?

Libuše Jarcovjáková: Berlin was a huge challenge for me when I moved there in the mid-1980s. I came here without the language, friends, money, and minimal knowledge of what life in the West meant. I managed to overcome all the obstacles, not to fall on my knees and start benefiting from the incredible resources that the city represented. I was fascinated by the multiculturalism, art, and freedom that Berlin radiated. This freedom came about despite the many scars of war that the city was still full of at the time. For me, Berlin was and remains a city that never leaves me, neither with its contradictions nor with its constant development and openness. It is a city that constantly challenges me to evolve as both an artist and a person.

The film about you and your breathtaking photography was made in the middle of the pandemic and has now been traveling to festivals large and small for a year. What experiences have you had with it?

Libuše Jarcovjáková: The film has taken on a life of its own as it travels from festival to festival. Each screening opens up new discussions, provokes unexpected emotional responses, and sometimes even connects people who find solace or inspiration at the intersections of personal history and collective memory. I am continually amazed by how many people across countries and cultures identify with some of the layers of the film. people. The range of reactions is wide and confirms that we have managed to bring to life universal themes that resonate in different periods and contexts of life.

After the film, exhibitions, books: What’s on the agenda for you?

Libuše Jarcovjáková: For me, staying sane and maintaining my ability to perceive the world in all its subtle nuances is key. I achieve this through creativity, photography, and writing – ways in which I defend myself against excessive pessimism and a skeptical attitude towards the present. I try not to succumb to the flood of information that could intoxicate me, and instead I engage in creative activities that allow me to maintain an authentic perspective on life and express my inner experiences.

Mehr Fotografie

Diesen Beitrag teilen