“Life as a breathing installation piece”: Vaginal Davis on her first major exhibition

Vaginal Davis, the legendary queer icon and cultural agitator, has called Berlin home for over two decades. Since relocating from Los Angeles, she has become a pivotal figure in the city’s underground and institutional art scenes, known for her genre-defying performances, radical aesthetics, and incisive political commentary. In this interview with Ahmed Awadalla Davis delves into her experiences in Berlin, her artistic journey, and the intersections of art, identity, and activism.

Zur deutschen Übersetzung dieses Interviews.

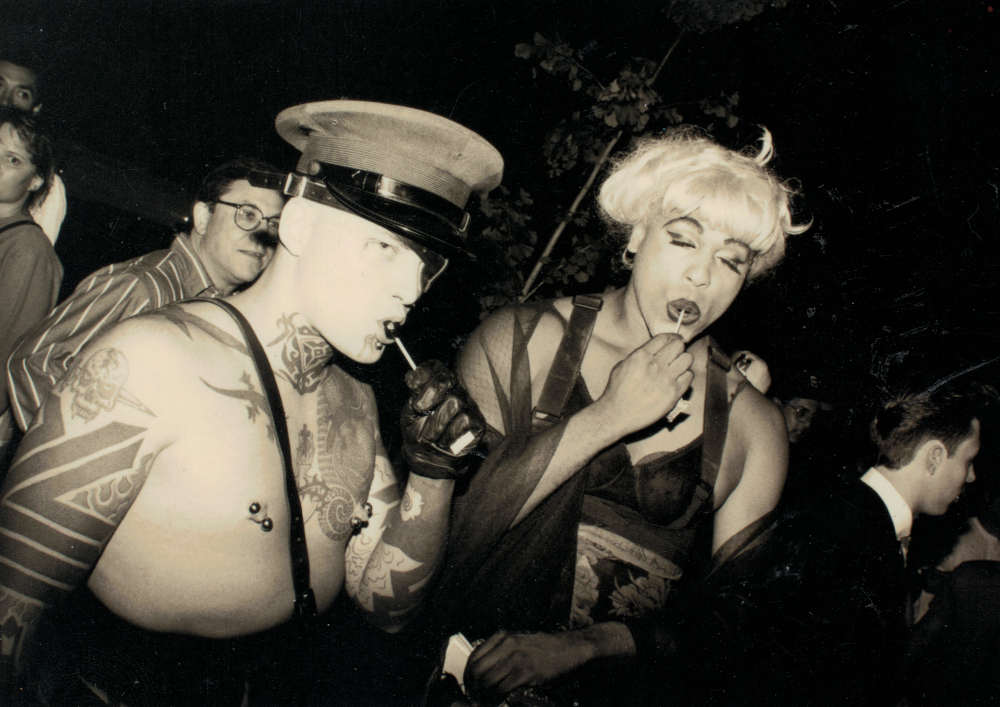

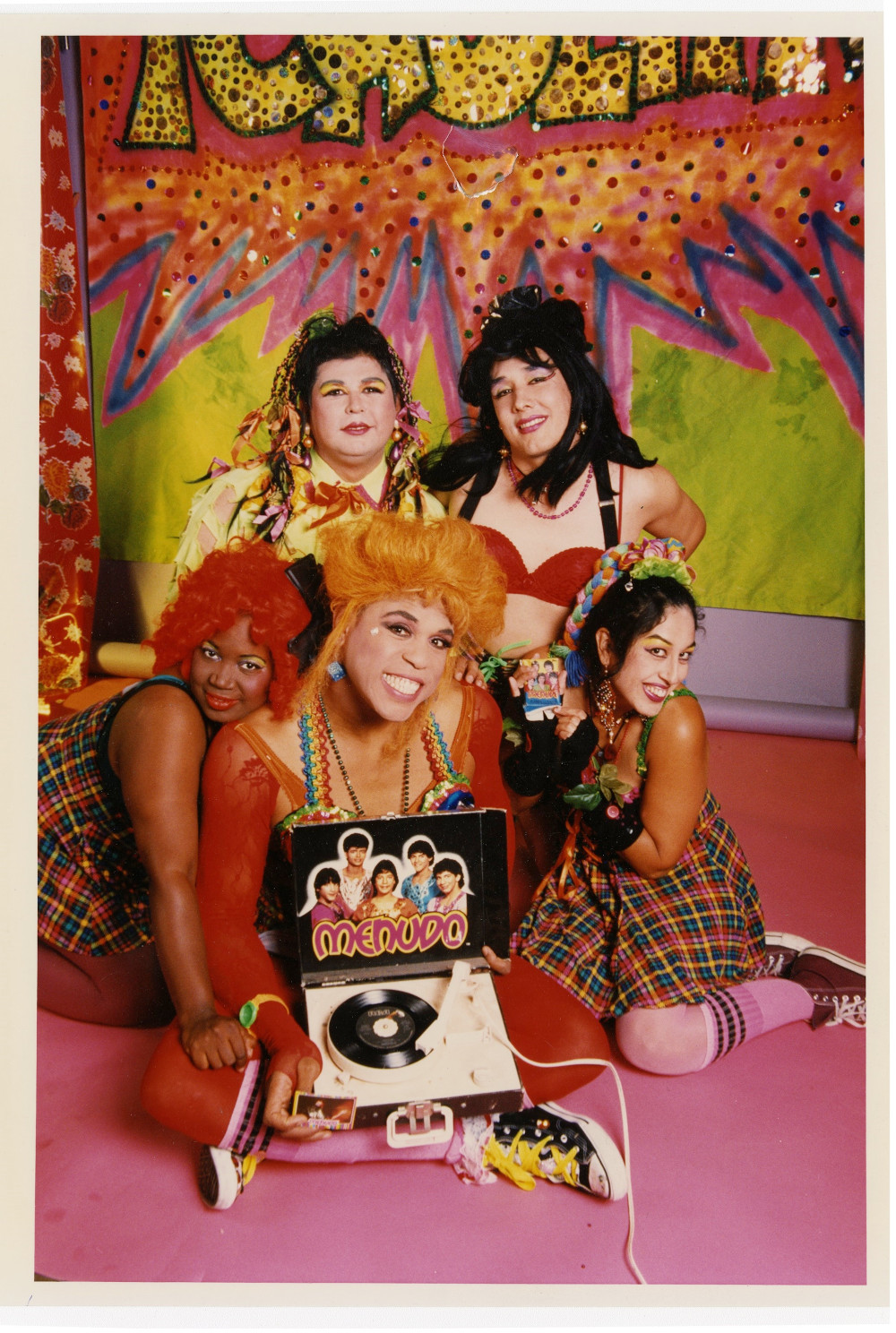

Davis’s first major solo exhibition in Germany, Fabelhaftes Produkt, is currently on view at Berlin’s Gropius Bau from March 21 to September 14, 2025. The exhibition offers a comprehensive overview of her multifaceted practice, featuring large-scale installations, paintings, video and film works, zines, texts, music, and performances. It also highlights her numerous collaborations, including the installation Choose Mutation with the Berlin-based CHEAP Kollektiv, showcasing photographs by Annette Frick. Fabelhaftes Produkt invites visitors into Davis’s universe, where punk meets glamour, queer activism intersects with Black counter-culture, and resistance coexists with desire.

Interview with Ms. Vaginal Davis

Awadalla: Ms. Vaginal Davis, thank you for sharing your time and life with us. Your work has offered so many of us—across generations and geographies—new ways to think about performance, politics, pleasure, and survival.

You’ve described Berlin as having a “raw poetic beauty in its bleakness,” and embraced its grumpy bluntness as a kind of relief from the Los Angeles you left behind. That sense of freedom—of finding room to breathe—is something many Black American artists have spoken about, especially in contrast to the relentless violence of the U.S. state. But Berlin’s reputation as a queer haven can sometimes obscure the structural inequalities that persist, especially for migrants, racialized people, and those outside dominant queer aesthetics. How has your relationship to the city evolved over the years? Do you feel Berlin itself has changed?

Vaginal Davis: My relationship with Berlin goes back further than the twenty years I´ve lived here. My first time in Germany and Berlin was in the early 1980s. Like most stupid Americans I had no sense of European Geography. I thought Berlin was in the middle of Germany. I hadn´t bothered to look at a map until I arrived by train, and to my dismay all of Berlin was in the east and that a fake western presence was created in this most eastern of cities close to the German/Polish border.

We should all be aware that there are no havens or safe spaces in this world or the next. Berlin certainly is no panacea. Because Berlin had been a divided city it developed its own pace and state of being at odds with how danger capitalism engulfed other major metros. That grace period is over. We are now facing a new form of economy that is unnamed, but makes advanced capitalism look like whistling Dixie. It’s all about nebulous plus and minus zeros.

We should all be aware that there are no havens or safe spaces in this world or the next. Berlin certainly is no panacea.

Vaginal Davis

The elites of this world aren’t really as wealthy as they claim. They can’t just walk into a bank vault and start counting their $moula. Money is indeed the root of all evil, of strife and upheaval. The wealth of the ruling class is all concentrated in a very dark cloud, a Beelzebub matrix that’s just based on speculation and computer-generated models and formulas of greed. Millionaire, Billionaire, Trillionaire. It’s all a scam, a grift, a big undulating fraud perpetrated to prop up the status quo. There aren’t any countries or nations anymore it’s just icky, dullard, Melba toast corporations and their high-tech industrial death complexes.

Awadalla: Your work has always been unapologetically radical—and calling yourself a drag terrorist feels like both a provocation and a declaration of intent. You’ve also famously said you were “too gay for the punks and too punk for the gays,” moving through spaces where you didn’t quite fit—but made space anyway. What does it mean to now have your work held at Gropius Bau, an institution so different from the underground scenes you emerged from? Does this kind of recognition resonate with the spirit of your earlier work, or does it create a new dynamic in how your art is perceived and engaged with?

Vaginal Davis: When I first started to receive attention back in Los Angeles I was still a teenager. I never thought of myself as radical, or a provocateur, I didn´t even think of myself as an artist. I also didn´t coin the phrase drag terrorist. The late NYU scholar Dr. José Esteban Munoz is responsible for that term. My origins were merely about being creative in an organic manner which felt natural for me at that particular time and place.

It wasn´t until the early 1990s that writers like Dennis Cooper and curator Lia Gangitano made me realize that I had amassed quite a body of work. My sexual frustrations have always fueled my artistic endeavors. The first big institution to recognize me was the Institute of Contemporary Art-Boston under the then very young curatorial lead of Lia Gangitano and Laura Nix from Lesbian performance collective Fishnet. Their festival Dress Codes was also an institutional first for Catherine Opie, Lyle Ashton Harris, and Carmelita Tropicana. I had always been distrustful of institutions as I feel that you can´t change them, they wind up changing you and not for the better. That is why in the 1980s and 1990s I never applied for any art grants. I figured that it was a pointless exercise as I wasn´t doing work that was remotely accessible to hardly any audience outside underground circles.

I never thought of myself as radical, or a provocateur, I didn´t even think of myself as an artist.

Vaginal Davis

I had my small following in Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York and Chicago via my indie art/punk band projects. When my zine Fertile LaToyah Jackson was one of the first of the queer zines to be distributed internationally by Tower Records & Books in the mid-1980s I garnered a loyal fanbase in cities like Toronto, Montreal, London, Rome and Paris, but I had no desire or aspirations to reach beyond that. I`ve never had a careerist type personality. I was always surprised when I received any attentions at all as I didn´t come from a bildungbürgerlich family or one with generational wealth. It’s always been a mainstay that poor people are never accepted into institutional spaces.

Getting invited to Boston, which was a racially charged city, felt weird, but I immediately bonded with Lia and Laura as if we had known each other all our lives. A few years later Lia left Boston and was curating for Thread Waxing Space in New York City where I became such a fixture most people thought I lived in New York.

By the mid-1990s, I was being invited to the city, at least five or six times a year. When Thread Waxing Space closed, Lia founded Participant Inc. a not-for-profit artist space that became like a second skin to me and so many others. In 2012 I had my first solo exhibition at Participant Inc which led to commercial gallery representation shortly after that and everything else culminating in this my first solo traveling museum exhibition.

So, it was something that happened very slowly in a grassroots DIY manner over decades. Anyone who has known me since the 1980s knows that I have been operating consistently pretty much the same way shifting my mode of operations in very tiny increments.

Awadalla: Throughout your practice—and especially in this exhibition—you’re generous with your references: from naming yourself after Angela Davis, to being inspired by the Black Panthers, to honoring the CHEAP collective, to dedicating an installation to Arsenal Kino, and the movies you watched growing up. You place yourself in relation, not isolation. Why has this kind of citation and relationality been important to you? What does it mean to build an artistic practice shaped by collectivity and interdependence, especially in a world that still clings to the myth of the individual genius?

Vaginal Davis: I have always worked in a collaborative mode. It’s just more interesting for me to form new intersectional societies and community groupings and not be isolated. My mother came into her own through the spirit of 1968 working with this lesbian separatist feminist group. That is the environment I was raised in and has shaped my entire outlook on life. Female driven and led groups have always been a given. I grew up in an all-female household without any male presence. I´m the youngest child with four older sisters. Living in Los Angeles, the city of the automobile, I never learned how to drive a car and I´ve never owned one. Public transport and riding a bicycle have always been my only mode of tranportation, so I immediately felt akin to Berlin living.

I have always worked in a collaborative mode. It’s just more interesting for me to form new intersectional societies and community groupings and not be isolated.

Vaginal Davis

The fearless leader of the CHEAP Kollektiv in Berlin is artist Susanne Sachsse with our Minister of Information being Marcuse Siegelstein. I´ve worked with CHEAP since its inception in 2001. The director of Arsenal Institute for Film and Video Kunst is Stefanie Schulte Strathaus where I´ve been a guest curator since 2007 with the film events Rising Stars, Falling Stars, and Contemporary Vinegar Syndrome. For the last twenty years I´ve been fortunate to work under such dynamic leaders as Hannah Hurtzig of Mobile Akademie Berlin, theorists Nanna Heidenreich and Juliane Rebentisch, so nothing I do ever is ever shored in a vacuum.

Awadalla: We’re grateful for the personal archive you’ve shared in this exhibition, and the window it opens into queer life in L.A. One detail that stood out was that some of your early events were daytime happenings—not the usual late-night club scenes we tend to associate with queer life. There’s something quietly radical about creating space for connection, glamour, and mischief in the light of day. Was this intentional? And how do you think when something happens shapes how we imagine queer community and visibility?

Vaginal Davis: I didn´t create the template for daytime performance, music and art events. It’s something that was molded into underground circles in Los Angeles history from the turn of the last century to the punk and post-punk eras. I just pussy footed or piggy backed onto something that had already existed. My big influence was the Theoretical Happenings that were first held in the Leather Bar The One Way in the historically radical leftist Silverlake District in East Hollywood on Sunday afternoons in the early 1980s. A queer art collective consisting of Carol Cetrone, Jim Van Tyne, Debbie Patino and Jack Marquette created this long running series of events that lasted for over a decade off and on.

I love seeing what people look like in broad daylight, and also you can get away with murder because the Vice Squad of the Los Angeles Police Department doesn´t investigate transgressive events that take place in daytime hours so you can avoid authoritarian scrutiny and censorship.

Los Angeles is an official sister city to Berlin but it’s not an all-night town as things close at 2am. My punk rock club and performance space Sucker at the Garage was held at the oldest gay bar in Los Angeles for five years from 1994-1999 every Sunday from 3pm to 11pm. The first year of the club I still had a day job at UCLA´s Placement and Career Planning Center so being able to get a good night’s sleep was paramount for me.

Awadalla: There’s a palpable sense in your work that life itself is your medium; the archive isn’t just what’s preserved but also what’s performed, hinted at, or deliberately withheld. The idea of the Lebenskünstlerin (the artist of life) feels especially alive in your apartment-based exhibitions, the stacked books that were never written, the idea of ‘making a scene’. What does it actually feel like to live this way? Is it liberating? Is it exhausting? What are the stakes of making your life your canvas?

Vaginal Davis: To live a life as a living, breathing installation piece is both liberating and highly exhausting. It’s hard to turn oneself off and find a correct balance, as I tend to give my all to everyone and everything until there is nothing left for me. I am an introverted person who has forced themselves into the role of an extrovert.

Friends and acquaintances alike would joke that they were afraid I would art direct their very lives, and they would wind up leaving my atelier collaged with images and text covering their person. Thank Goddess Hecate for therapy and for lesbian processing which involves constant and thorough reflection.

To live a life as a living, breathing installation piece is both liberating and highly exhausting. It’s hard to turn oneself off and find a correct balance, as I tend to give my all to everyone and everything until there is nothing left for me.

Vaginal Davis

Awadalla: Your work has always carried the shadow—and the shimmer—of HIV und AIDS. From your zines and performances of the 1980s to the final room of this exhibition, the virus is present: lingering, shapeshifting. Mainstream conversations around HIV und AIDS often stay fixed on prevention, safety, and responsibility—frameworks that can be necessary, but also deeply normative. What other stories, ethics, or forms of intimacy emerge when we speak of living with disease, rather than trying to erase it? What lessons from the past remain unheard?

Vaginal Davis: I´m 64 years old so I was part of that earlier generation whose youth was spent living in the spectre of HIV und AIDS. I´ve lost so many friends and collaborators to that virus. I was never at risk for catching HIV as I was thought of as being quite sexually repulsive by most men I came in contact with. I really didn´t possess the sex appeal needed to attract sex partners and lovers so in that way I may have dodged a bullet.

I also was very risk averse coming from a fundamentalist religious background, so I had a lot of damage that kept me very passive, so I participated in very limited experimenting with sex and drugs. I certainly regret not taking more risks in life, as it has left me a little stunted.

It’s ironic that I do have a chronic auto immune illness of late onset type one diabetes which is actually much more debilitating than if I had contracted HIV. My HIV infected friends and colleagues take less medications. Even if one manages diabetes perfectly, your life expectancy will be minus fifteen years.

Exhibition

Vaginal Davis: Fabelhaftes Produkt, 21 March to 14 September 2025, Gropius Bau, Niederkirchnerstraße 7, 10963 Berlin.

More Art

Diesen Beitrag teilen